With its heightened characters - all basically Brit stereotypes of the period - and anarchic sense of humor, the movie is a perfect vehicle for Grant’s customarily manic persona, as he contorts his lanky frame into ever more angular postures and spouts chiseled tirades against the inequalities of the system. Not until he gives up his middle-class pretense at poverty, and experiences the real thing in a grungy working-class district away from his supportive friends, does Gordon really grow up and make some genuine life choices.

And to add to everything, Gordon’s attempts to have sex with Rosemary don’t get much beyond first base. The glamour of being a penniless artist starts to wear off when the rejection slips come in. Gordon, however, is not to be stopped, and, to suffer like any artist in the cause of inspiration, lodges in a single-room, suburban apartment while working as an assistant in a bookstore. Gordon feels his artistic side is not being fully utilized by snappy one-liners for hair lotion and health drinks, and promptly resigns (after negotiating a raise) to become “a poet and a free man.” He already has one slim tome published, and is emboldened by a review that he “shows promise.” Others in his circle are not so sure, from the quietly sensible Rosemary, through his long-suffering sister, Julia (Harriet Walter), who waits tables in a tea shop, to his snooty publisher, Ravelston (Julian Wadham). Grant) is a star copywriter at an ad agency where his girlfriend, Rosemary (Helena Bonham Carter), is a designer.

Vet playwright-scripter Plater, whose ear for nuanced dialogue stretches back to the ’60s, stays close to the original storyline and characters while giving the dialogue a contempo boldness.

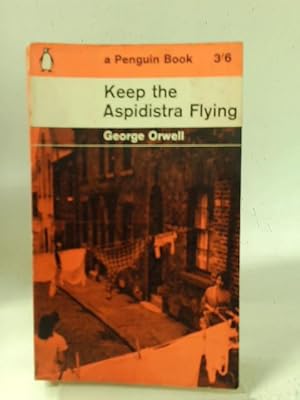

An ironic look not only at Blighty’s class-conscious society and the economics of publishing, but also at the pretensions of being an “artist,” the book is based on his own experiences on the bread line and working in a bookstore while trying to forge a career as a writer during the late ’20s and early ’30s. until 1955, predates his famous political allegories, “Animal Farm” and “1984,” by a decade or more. Orwell’s novel, which first appeared in 1936 but was not published in the U.S.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)